Complicit Construction: The Role of Architects in the Prison Industrial Complex (A Ten-Year Overview, 2012-2022)

Before looking ahead, you must look behind.

—US Federal Bureau of Prisons, History Section Header

What is, so to speak, the object of abolition? Not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society.

—Fred Moten & Stefano Harney, The University and The Undercommons

Invisibility, with regard to Whiteness, offers immunity. To be unmarked by race allows you to reap the benefits but escape responsibility for your role in an unjust system.

―Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code

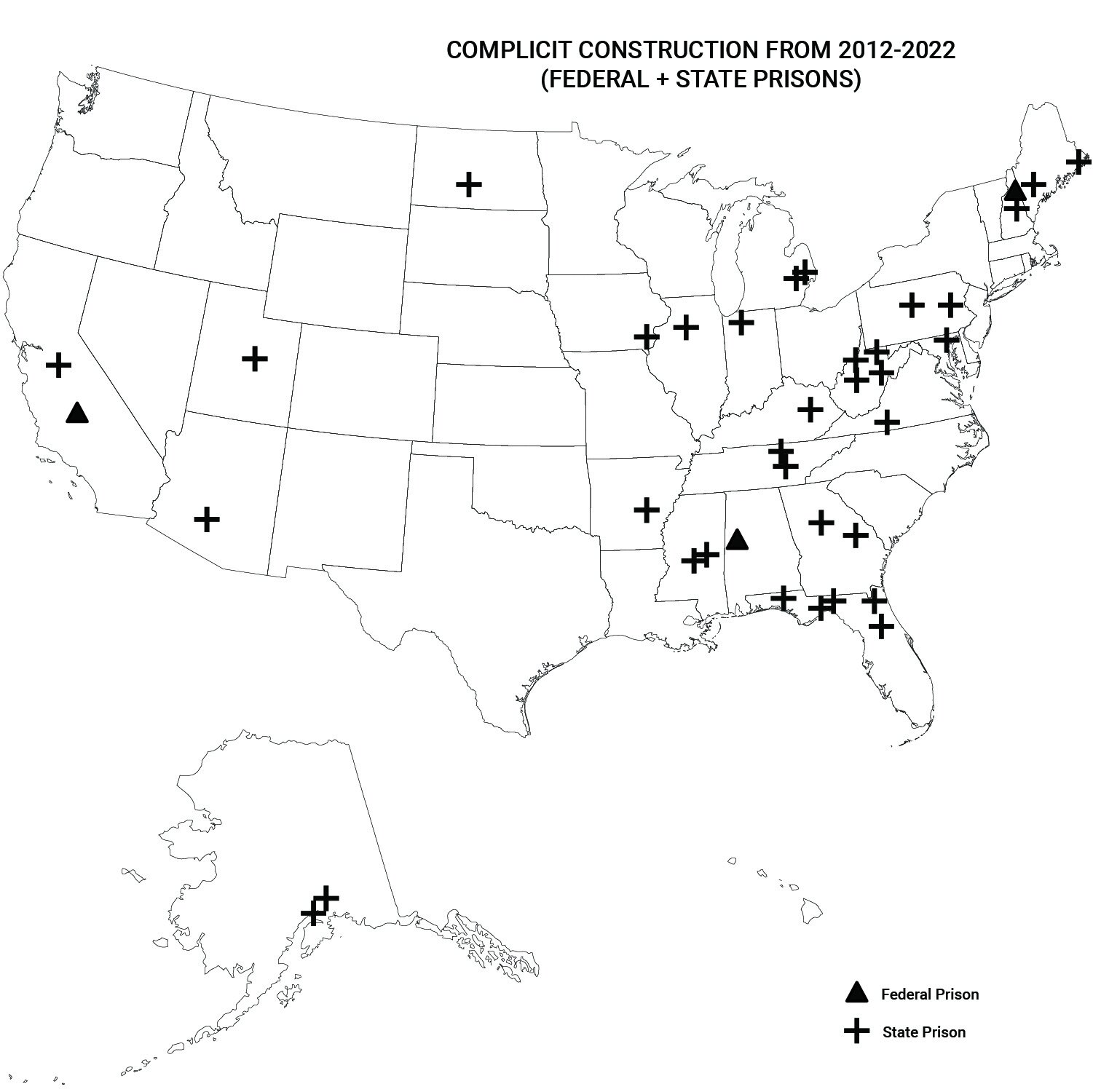

Between 2012-2022, 37 new federal and state prisons, with a capacity for 37,290 new inmates, were built across 25 states in nearly every region of the US. All these new prisons were designed, permitted, and constructed by architecture, construction, and engineering (ACE) firms. In this project, I define these buildings as Complicit Construction projects: infrastructure designed to maintain hegemonic violence and state order. Global firms such as AECOM, HOK, DLR, boutique firms such as NADAAA, and even design studios such as Frank Gehry’s at Yale in 2017 legitimize architects’ roles as thought leaders for future carceral structures. The American Institute of Architects, architecture’s professional organization, has an Academy of Architecture for Justice that hosts conferences, publishes journals, and creates a community for “high-quality planning, design, and delivery of justice architecture.” In short, Complicit Construction implicates architecture as an instrument of state violence.

As a design student at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), this research is a means of co-implication for me. In the words of professor Joe Kincheloe, “Co-implication refers to the idea that all of us share histories as well as certain responsibilities: ideologies of race define both black and white peoples, just as gender ideologies define both women and men.” As a non-Black person of color, I understand that my liberation is directly tied to the abolition of prisons and working to prevent the carceral state from inflicting further violence. This research situates architects within the prison industrial complex, specifies where the latest carceral spaces were built, and ties these firms to the institution and alumni of Harvard Graduate School of Design.

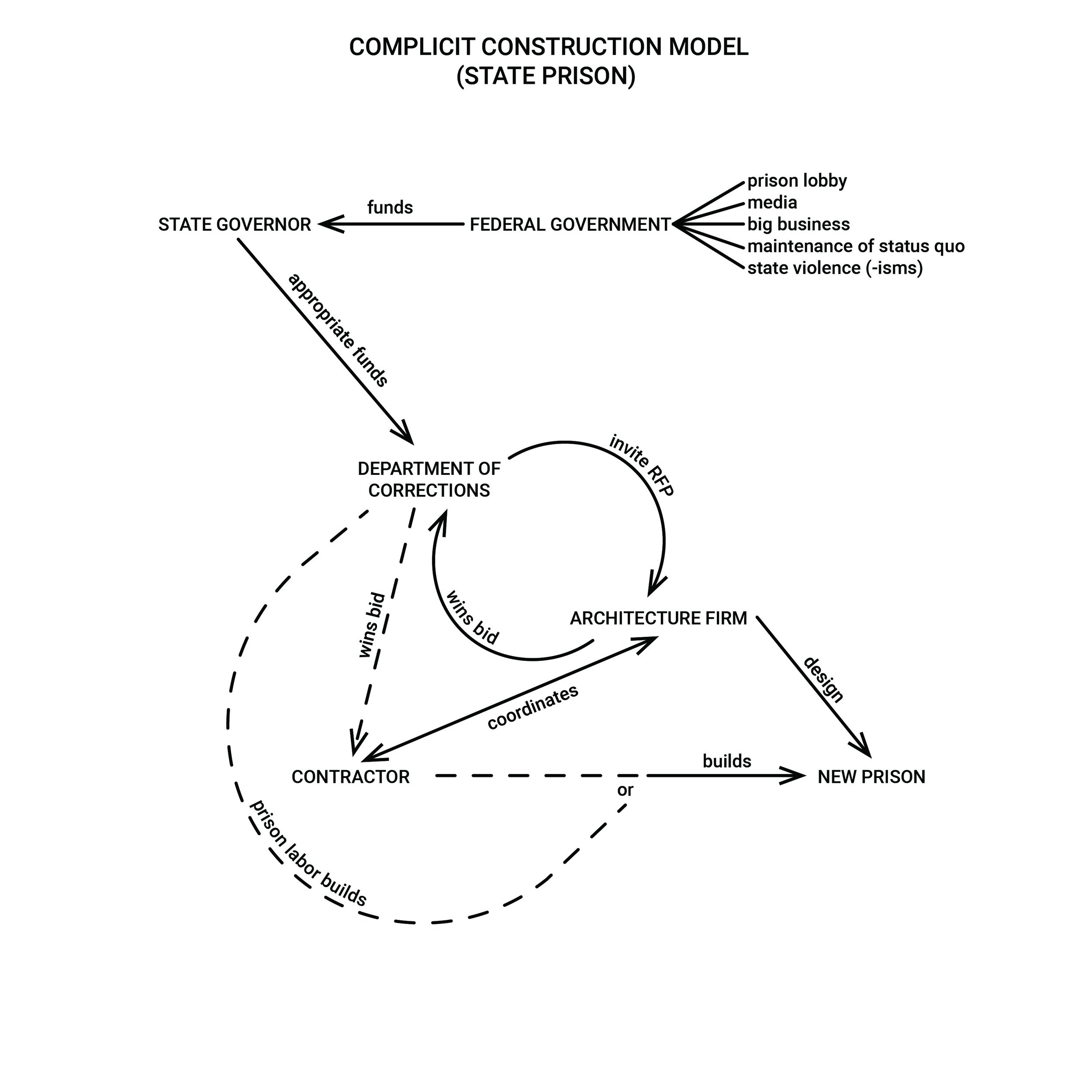

This diagram maps the Complicit Construction Model, as institutions influence the state to fund Departments of Corrections that contract ACE firms to construct new prisons.

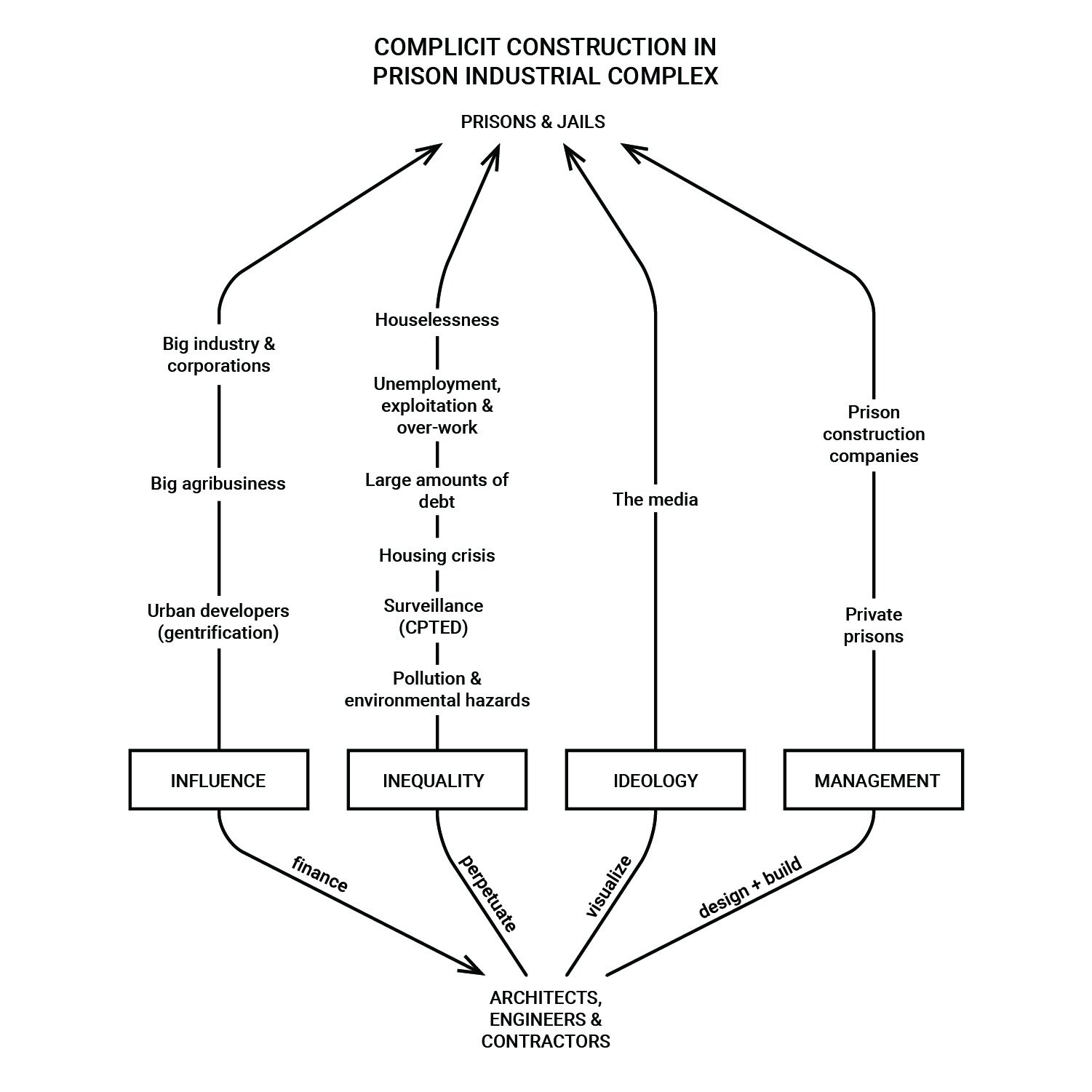

As theorized by abolitionist organization Critical Resistance (founded by a coalition that includes Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore) “the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.” The PIC directly targets Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities through harsher sentencing, violent policing, discriminatory surveillance, exploitative unpaid and underpaid labor practices, and the propagation of mass incarceration. In the Complicit Construction model, ACE firms are influenced by financial incentives to build prisons and jails, perpetuating inequality, visualizing “justice” ideology, and designing structures that maintain the carceral state.

The Complicit Construction Model is directly tied to the Prison Industrial Complex through relationships of influence, inequality, ideology and management.

To measure the scale of impact, I sought to document all the federal and state prisons constructed from 2012-2022. Ten years is a standard unit of time but also marks 10 years since Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teen, was murdered in the street by George Zimmerman, whose trial set into motion the Black Lives Matter Movement. The scope of research does not cover county or city jails, courthouses, border crossing stations, police headquarters, or ICE detainment centers which are also Complicit Construction projects. No centralized database existed for federal and state prison construction, so my research began with extensive searches through the Federal Bureau of Prisons and each state Department of Corrections website. After compiling an initial list, I searched through prison websites and made direct calls to prisons, local newspapers, and ACE firms. In a few instances, I filed Freedom of Information requests to find the corresponding ACE firms.

Map shows 37 new federal and state prisons completed from 2012-2022. The new prisons have a collective capacity of 37,290 inmates.

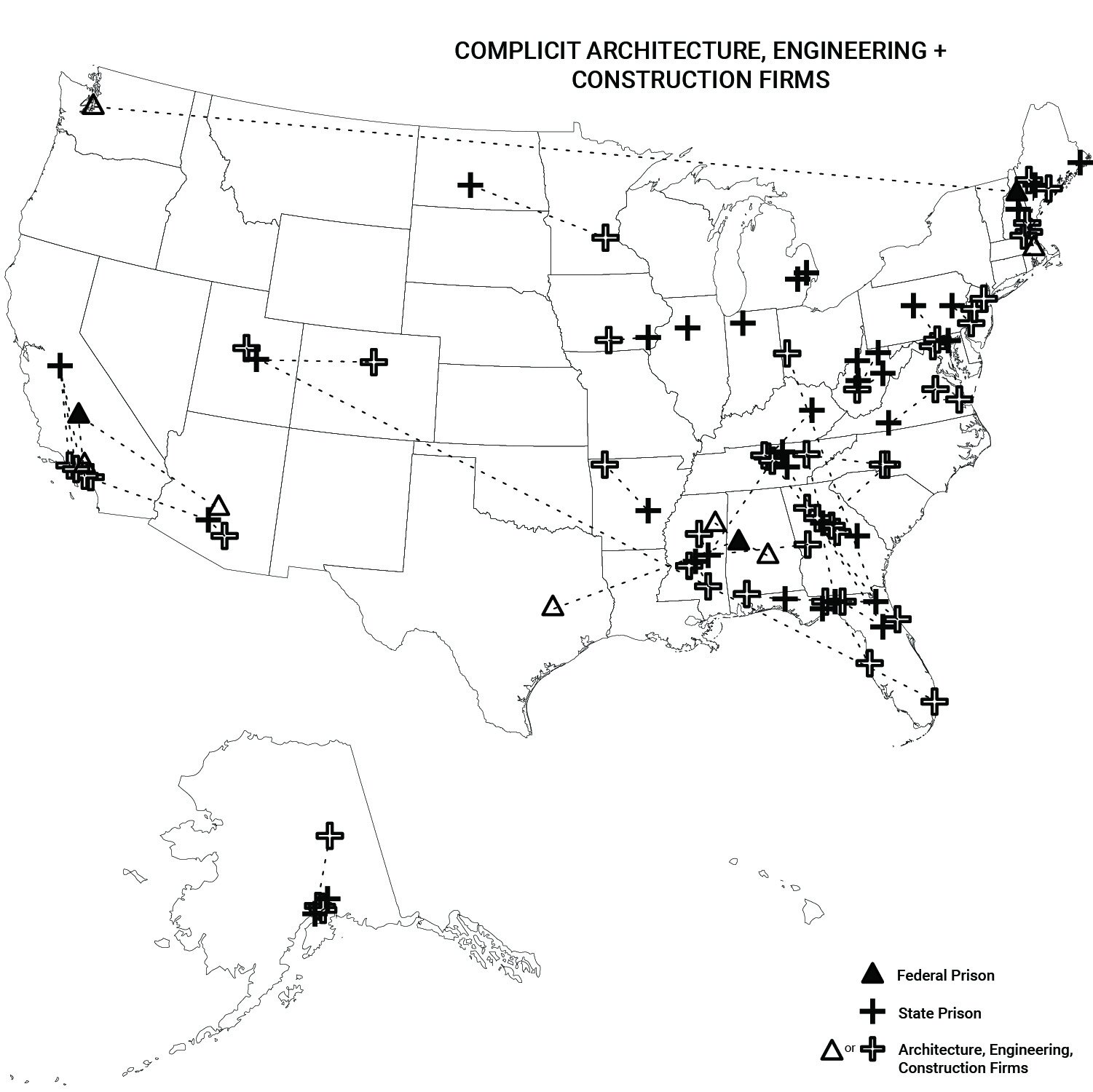

Thirty-two architecture or integrated design/build firms designed the 37 new prisons. Many of the contracted ACE firms are based in the states of the constructed prisons, which is unsurprising given the nature of government contracts. Several firms did work with national architecture firms, such as DLR and HOK, as subcontractors during the design and construction process.

Map shows federal and state prisons completed from 2012-2022, linked to the 32 ACE firms that designed and constructed each prison.

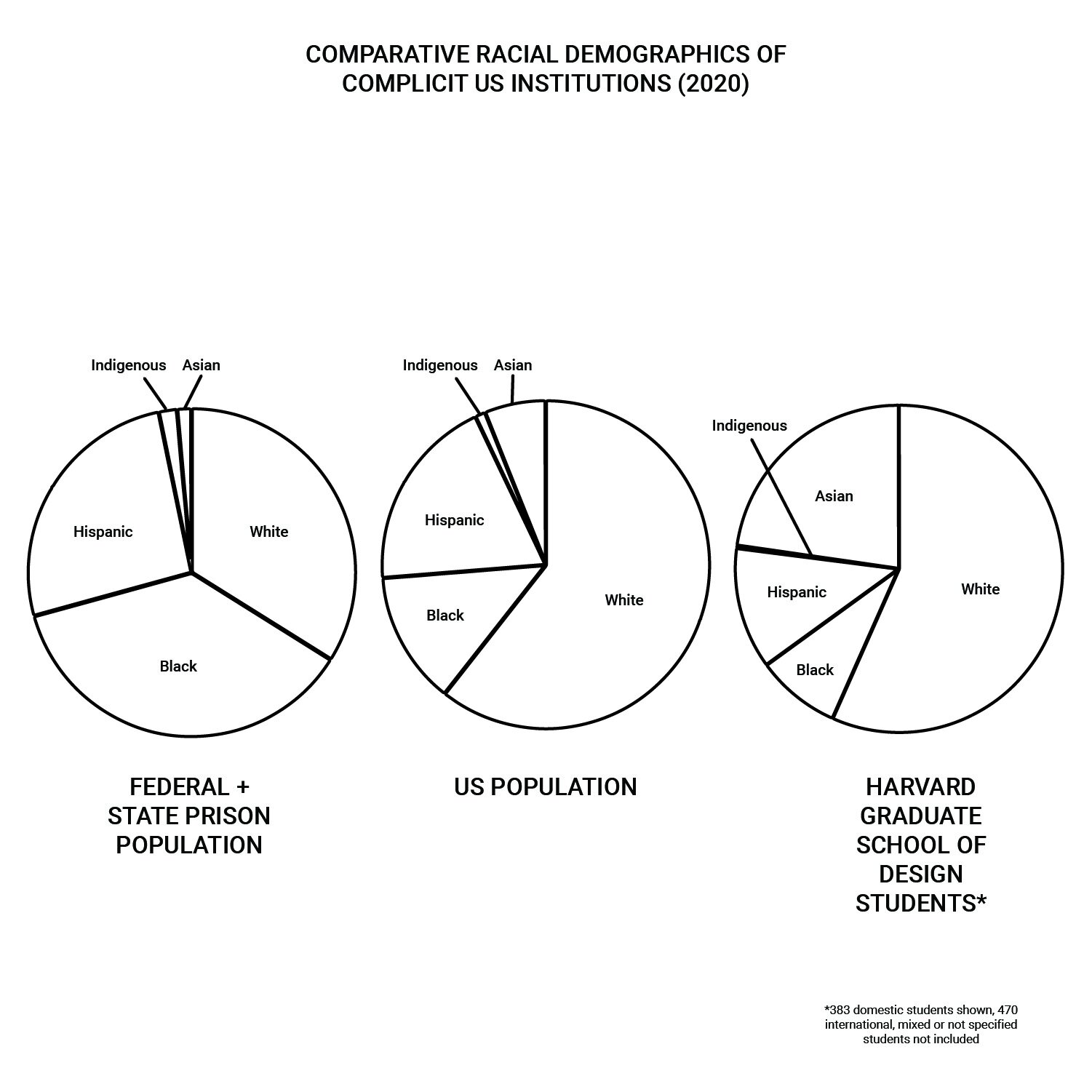

This research was funded by the Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund at Harvard Graduate School of Design, which “exists to raise awareness of how race, racism, and racial injustice affect society.” As a current GSD student, I applied for this funding to co-implicate the GSD in the immediately recent past of prison construction. Taking account of how GSD alumni participate in the violence of Complicit Construction is critical to building discourse on the school’s stated commitments to anti-racism work. In total, 27 GSD graduates currently work for those firms, as determined through a LinkedIn search of the firms (the Harvard Alumni Office denied my request to cross-reference the firms with their alumni lists). GSD has made several commitments to anti-racism work, this accounting is critical to building discourse on how to move “Towards a New GSD”, an imperative that GSD Dean Sarah Whiting has explicitly prioritized. As visualized in the pie charts below, the racialized institutions of prisons and Ivy League schools communicate the violence inflicted by a predominantly white institution on predominantly Black and Brown incarcerated people.

Implicating the GSD’s contemporary prison designers is an invitation to consider refusal as a valid and necessary option as schools and practices uphold their own ethical obligations and take responsibility for building more just futures.

Pie charts show uneven racial representation present in federal and state prisons and Harvard Graduate School of Design compared to the US population.

I have been radicalized by many things over the course of my life, but the words and concepts taught by the Black Lives Matter movement in 2012 are integral to my interest in this work of anti-racist design research. This research was done in tandem with my work in Design As Protest and Dark Matter University, two collectives working towards design justice in the practices and education of the built environment. As a designer-organizer, I am also using this research to contribute to abolition movements across the world, specifically standing on the shoulders of Designing Justice, Designing Spaces, and Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility.

On the US Federal Bureau of Prisons website history section, the page header reads, “Before looking ahead, you must look behind.” As we look towards an ethical future for the architecture industry, there is much to learn by looking very recently back, positioning our next work as accountable to the harm that preceded us. In February 2021, the Massachusetts Designer Selection Board reviewed their Request for Qualifications to build a new women’s prison, with five submissions from ACE firms. The work of stopping, dismantling, rejecting, and defunding Complicit Construction continues for all of us.

— Special thank you to Charlotte Malterre-Barthes for advising me on this research and always asking tough questions.

References

“Academy of Architecture for Justice.” Academy of Architecture for Justice - AIA KnowledgeNet, 2022. https://network.aia.org/communities/community-home?communitykey=6cb91d7c-05dc-4b48-97 ea-b36b6034093e.

“Detention.” DLR Group. Accessed July 29, 2022. https://www.dlrgroup.com/sector/detention/.

“Federal Bureau of Prisons.” BOP, 2022. https://www.bop.gov/about/history/timeline.jsp.

“GSD Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund.” Harvard Graduate School of Design, February 23, 2022.

https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/commitment-to-diversity-inclusion-and-belonging/gsd-racial-equity- and-anti-racism-fund/.

“Justice.” AECOM. Accessed July 29, 2022. https://aecom.com/ca/markets/government/justice/.

“Justice.” HOK, July 18, 2022. https://www.hok.com/projects/market/justice/.

Kincheloe, Joe L. Critical Pedagogy Primer. New York, NY: P. Lang, 2008.

Massachusetts Designer Selection Board Meeting Minutes, February 2021, Massachusetts State Records, Accessed July 29, 2022. https://www.mass.gov/doc/minutes-of-the-1009th-meeting/download.

Moten, Fred, and Stefano Harney. “The University and the Undercommons.” Social Text 22, no. 2 (2004): 101–15. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-101.

Slade, Rachael. “Is There Such a Thing as ‘Good’ Prison Design?” Architectural Digest, April 30, 2018. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/is-there-such-a-thing-as-good-prison-design.

Straughan, David. “From 1990-2005, the U.S. Built a Prison Every 10 Days.” Interrogating Justice, August 19, 2021. https://interrogatingjustice.org/ending-mass-incarceration/prison-every-10-days/.

Wachs, Audrey. “This Design Team Has Ideas for a Better, More Humane Jail System.” The Architect's Newspaper, July 14, 2017. https://www.archpaper.com/2017/07/this-design-team-has-ideas-for-a-better-more-humane-jail-system/.

“What Is the PIC? What Is Abolition?” Critical Resistance. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://criticalresistance.org/mission-vision/not-so-common-language/.

Whiting, Sarah (2020, June 15). Toward a New GSD. Harvard Graduate School of Design.Retrieved March 27, 2022, from https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2020/06/toward-a-new-gsd-a-letter-from-dean-sarah-m-whiting/.